DISCLAIMER: This work was produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union.

(Re) collecting Natural History in Europe is a research project that examines how natural history and ethnographic collections are curated and displayed, with a particular focus on European museums. This first phase of the project centers on the interpretation of collections within the context of Portugal's colonial history with Brazil.

When I first got in touch with the National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon, I was particularly drawn by the colonial connection between Brazil and Portugal. And when the museum accepted to be my host institution for the Mobility Fund Culture Moves Europe, I began searching for a place to stay during the two-week residency starting in March. To my surprise — and perhaps with a touch of irony — I booked an apartment on Rua dos Navegantes, or "Street of the Navigators."

The name Rua dos Navegantes immediately evoked Portugal's maritime history, bringing to mind the so-called "Age of Discoveries", when Portuguese explorers inscribed themselves into European history as discoverers of lands that had long existed but were disregarded as part of a different, "uncivilized" world.

Arriving in Lisbon, it is difficult to escape the coastal atmosphere: the presence of water — whether the Tejo River or the Atlantic Ocean — is constant, and the culture of seafood is omnipresent. Yet my interests were not in the open horizons of the sea but rather in the confined and often inaccessible spaces of museum storage rooms, where collections that had long travelled in those waters, are now preserved, categorized, and sometimes forgotten.

My first encounter with the National Museum of Ethnology's reservas visitáveis (visitable collections) challenged my expectations. Though located in the basement, with the lights off before our arrival, this was not a forgotten or neglected space. Rather, it was a site of active engagement, where history is being continuously reinterpreted. Explored not only by scholars and the general public but also by Indigenous visitors — those who hold the deepest knowledge of these objects, the beautifully arranged, climate-controlled cabinets held everything one might expect in an ethnographic collection, classified according to Western categories. However, this framing was not overlooked by Daniel, the knowledgeable anthropologist who guides the visits, that happen twice a day. Notably, some of the objects on display had undergone a process of musealization — a transformation that stripped them of their original spiritual or ritual significance, recasting them as museum artifacts within a Western epistemology. This distinction — possibly irrelevant to Indigenous peoples — underscores the importance of a collection stewarded by professionals well-versed in decoloniality, provenance, and the complexities of ethnographic display.

The museum's long-term vision to make its collections accessible to the public began with the opening of the Galerias da vida rural (Rural galleries) in 2000 and has since expanded to include the Galerias da Amazônia (Amazonian galleries). This initiative ensures that visitors can engage with a significant portion of the museum's holdings, rather than only the select pieces chosen for temporary exhibitions. Its innovative approach to collection accessibility, provided a compelling case study for how institutions can make their archives more transparent and participatory.

Among the most significant collections of the Amazonian galleries are those gathered by Victor Bandeira in the 1960s at the request of Jorge Dias, the museum's founder, and those acquired between 1999 and 2000 from the Waujá people of the Xingu. These collections, developed in dialogue with indigenous communities, offer an important counterpoint to the historical dynamics of ethnographic collecting, which often occurred without consultation or consent. Their presence within a space designed for accessibility and research represents a meaningful step towards rethinking how museums engage with cultural heritage.

The name Galerias da Amazônia, however, is not entirely accurate and could benefit from reconsideration. Many of the objects displayed come from Indigenous peoples outside the Amazon region, yet they are all categorized under this broad label. In a museum committed to decolonizing its collections, maintaining such a designation seems somewhat inconsistent. This classification risks creating a misleading impression, as Indigenous cultures across Brazil and elsewhere are diverse and distinct, each with its own histories, material practices, and cosmologies.

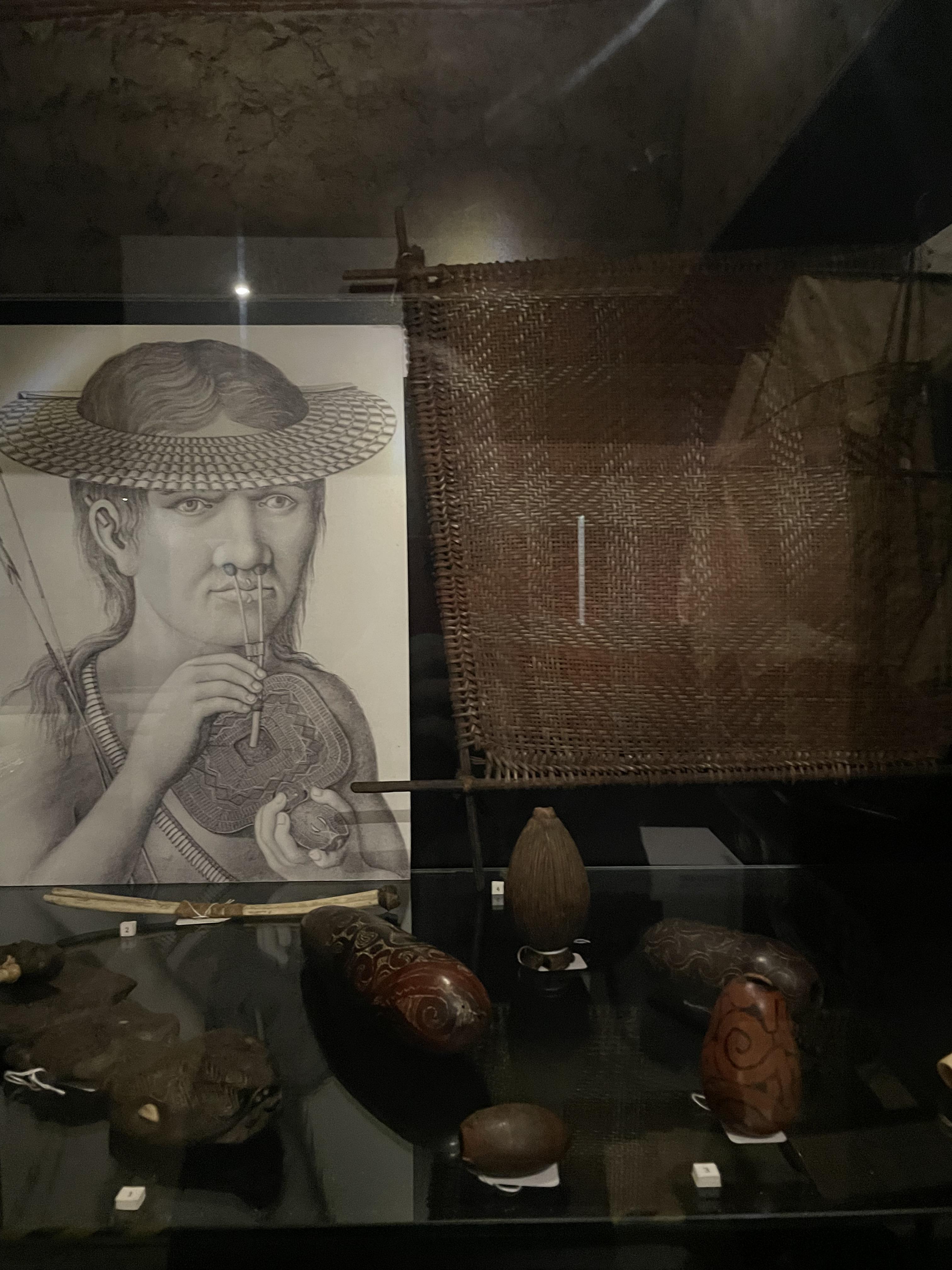

While in Portugal, I also visited the Academia de Ciências in Lisbon, where I had the opportunity to explore the collection of Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira, a Brazilian naturalist who gathered specimens and artifacts in the 18th century to the Portuguese crown. This collection was later scattered across institutions after Portugal was invaded by Napoleonic France. As a colonial collection, its remnants in the Academia de Ciências are poorly documented, a stark contrast to the collections in the National museum of ethnology, which were systematically acquired. The state of the Ferreira collection highlights the impact of colonial practices, with the objects now fragmented and lacking proper curation.

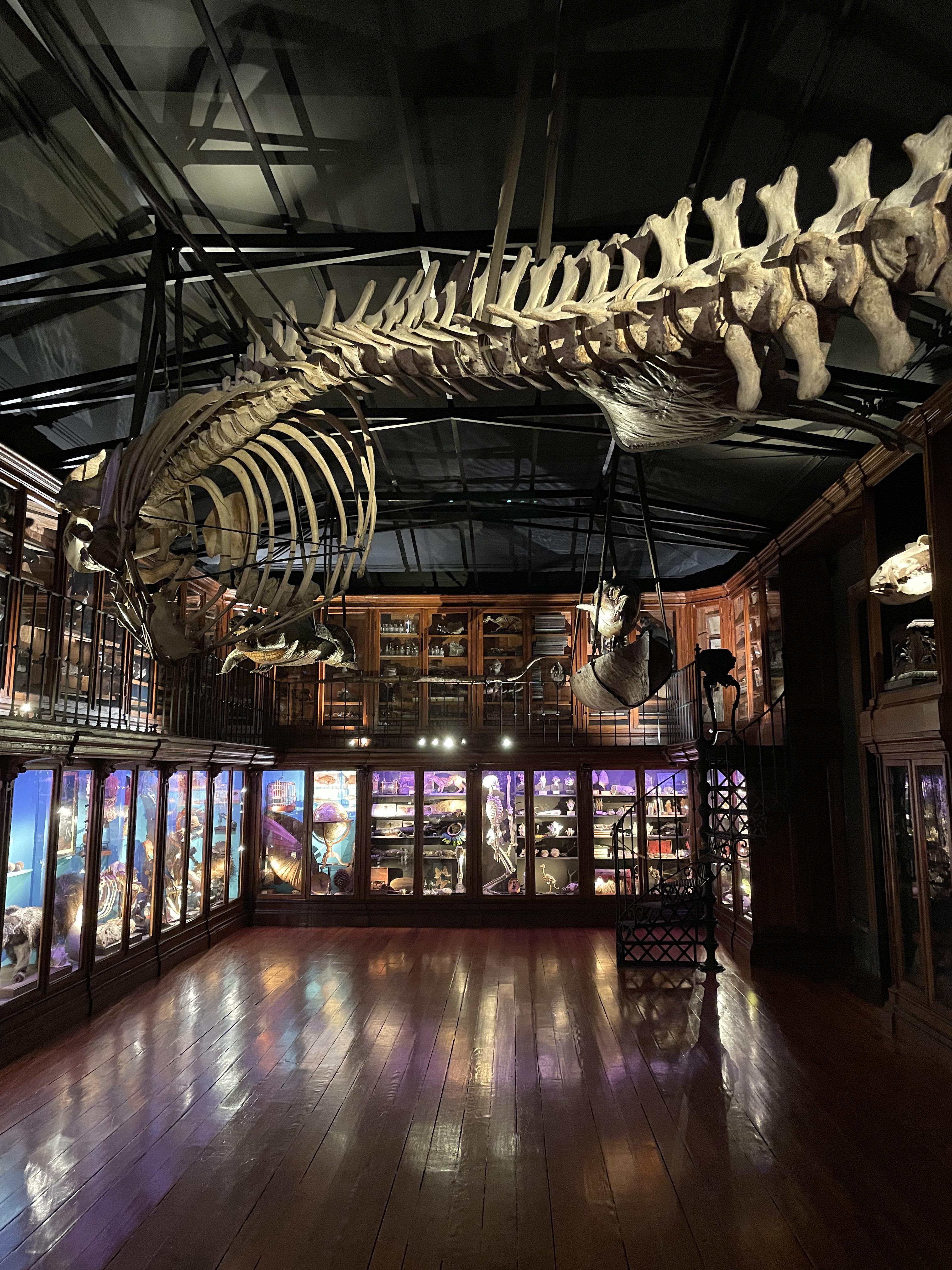

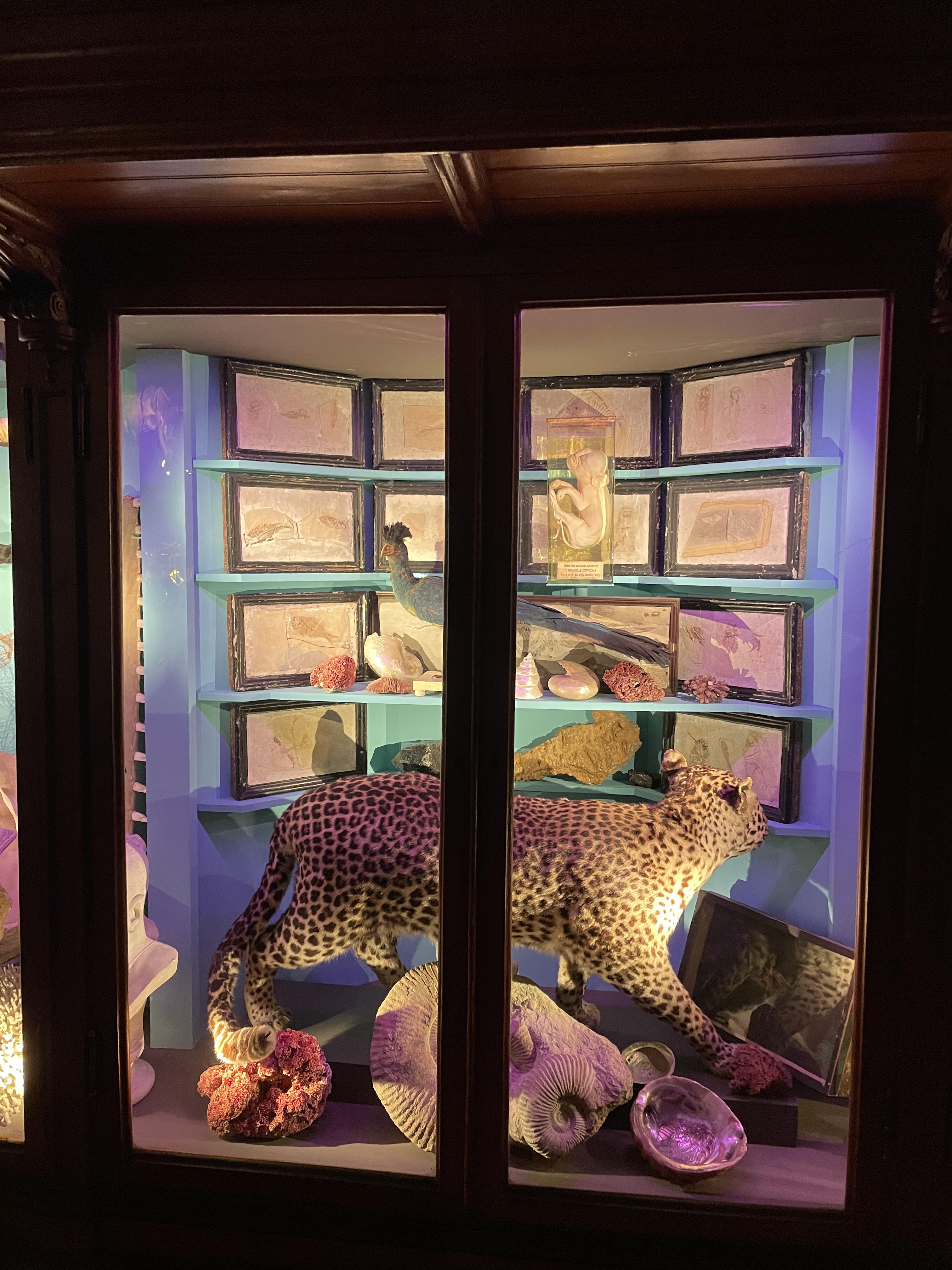

The Cabinet of Curiosities at the Natural History Museum of the University of Coimbra, another destination of the research mobility, highlights precisely why re-examining colonial collections is so important - the core objective of my project. Some of the objects displayed here are said to come from collections like the one in the Academia de Ciências, assembled by the Brazilian naturalist Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira. However, there is no definitive way to verify this, as the exhibition lacks captions or provenance details. The display, though visually striking and carefully arranged in the traditional cabinet of curiosities style, leaves many objects without context, their histories obscured. This state of fragmentation and undocumented provenance is not surprising, given the circumstances under which these objects were acquired - radically different from the negotiated purchases that shaped the National Museum of Ethnology's collections. Rather than a flaw, this lack of documentation underscores the enduring need for research and reinterpretation, a challenge at the heart of decolonial museum practices.

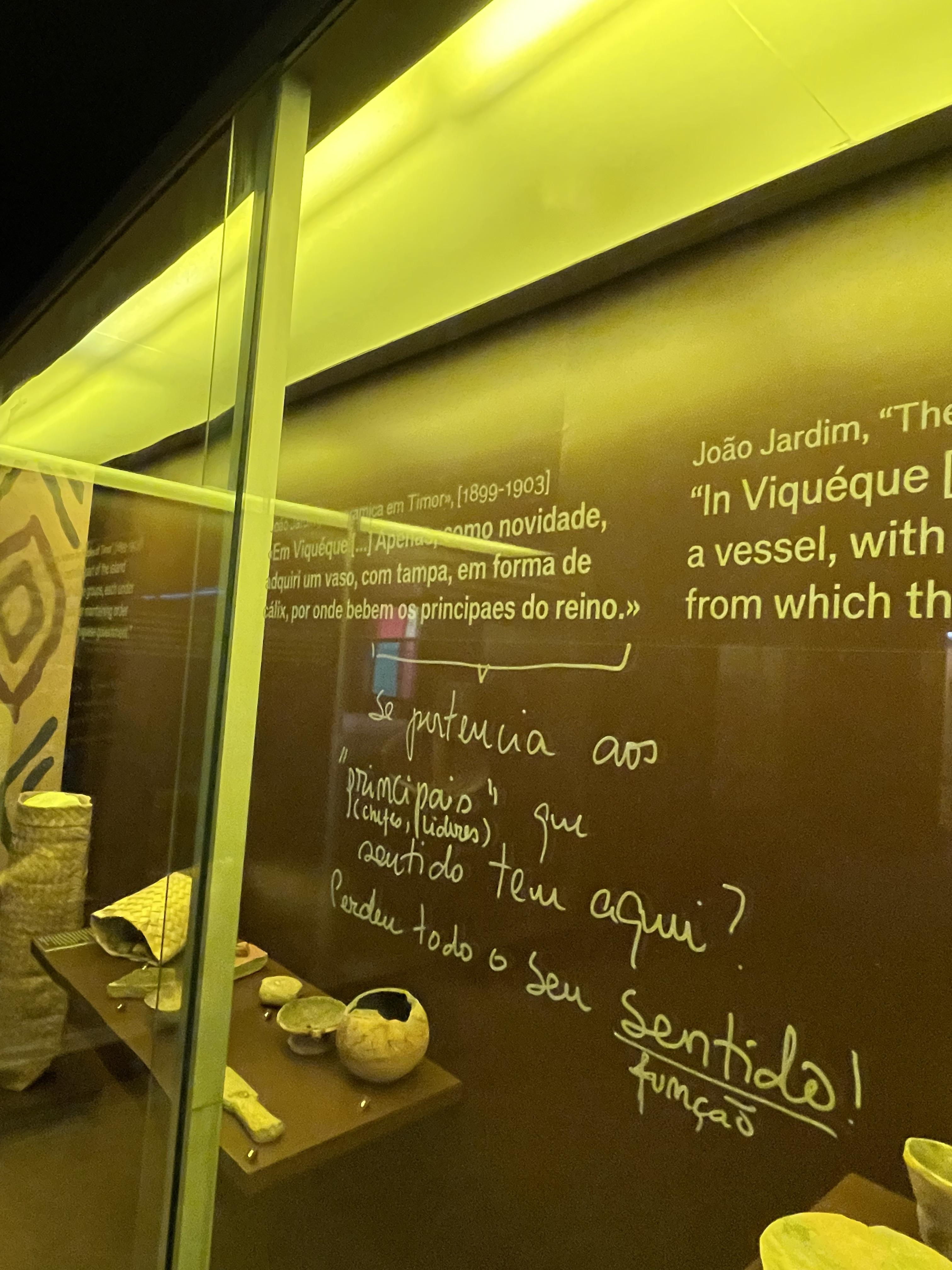

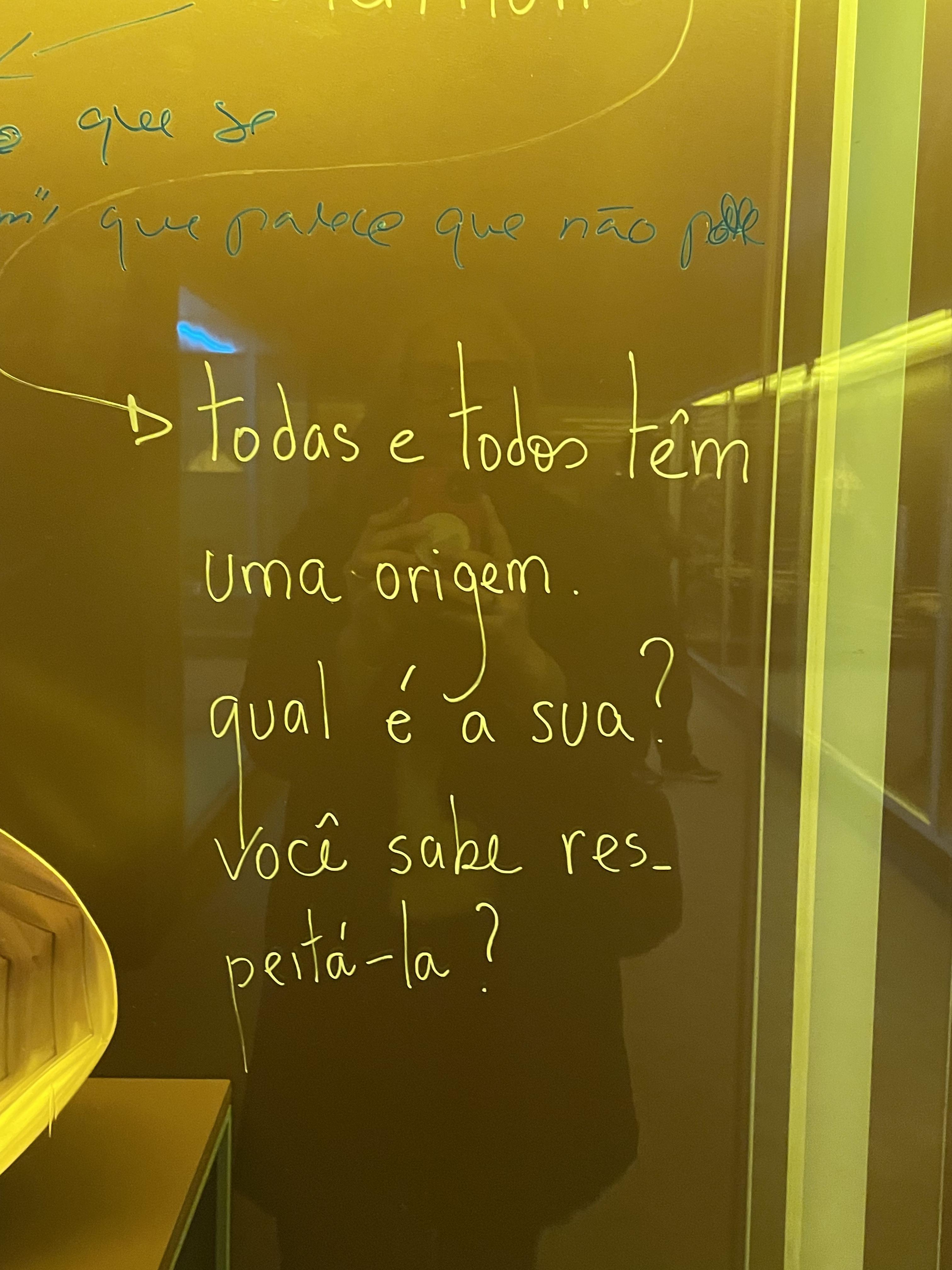

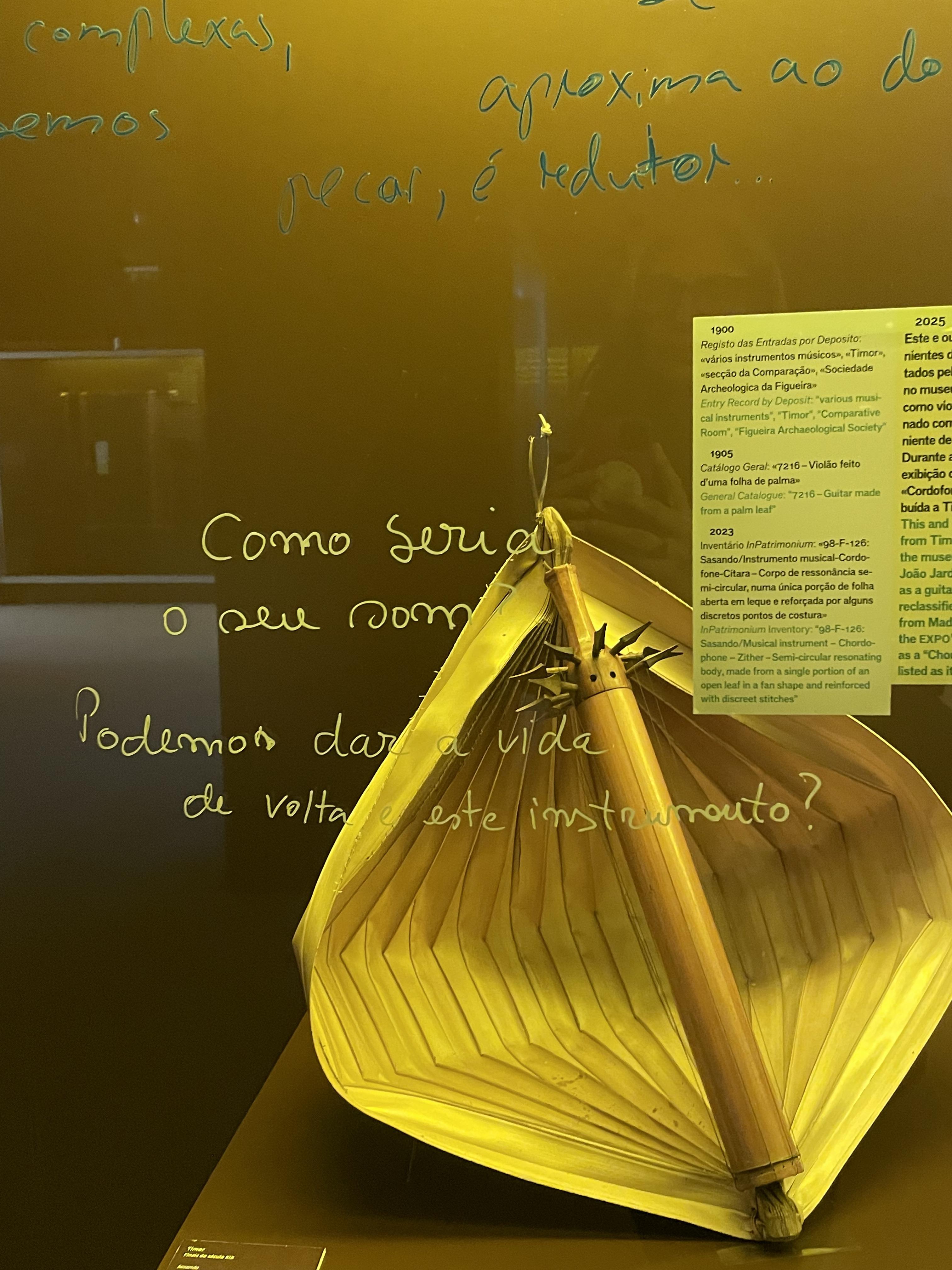

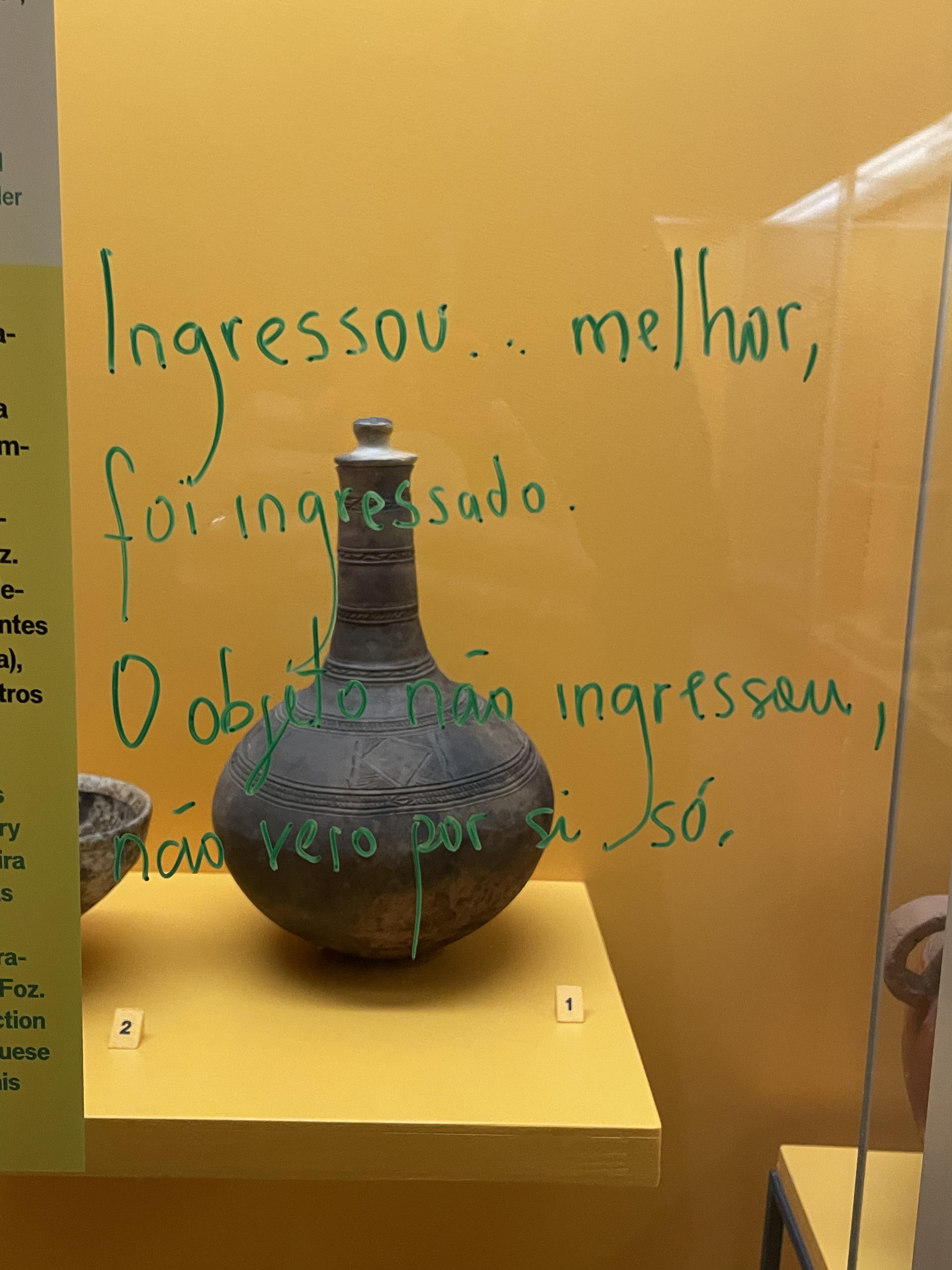

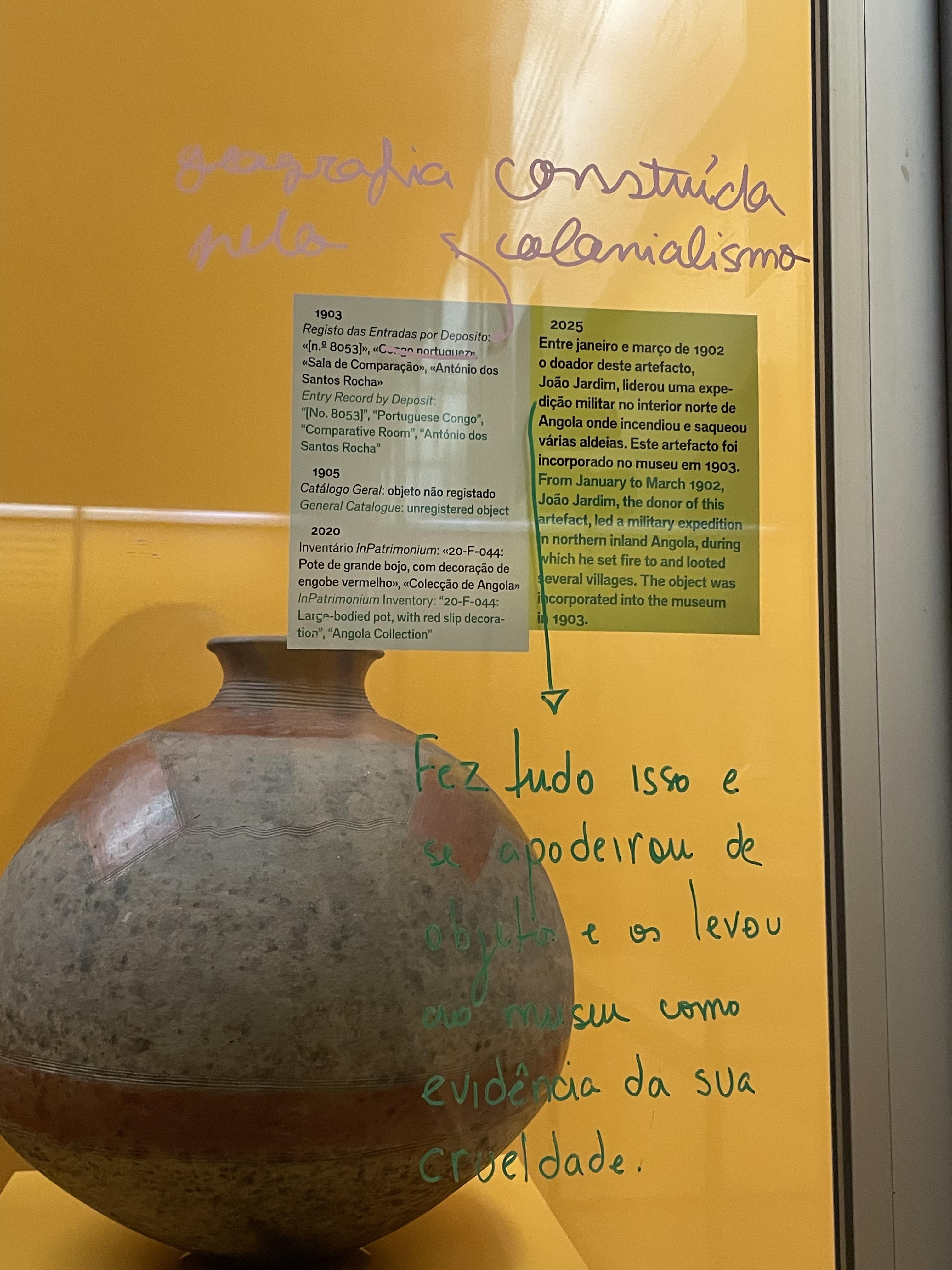

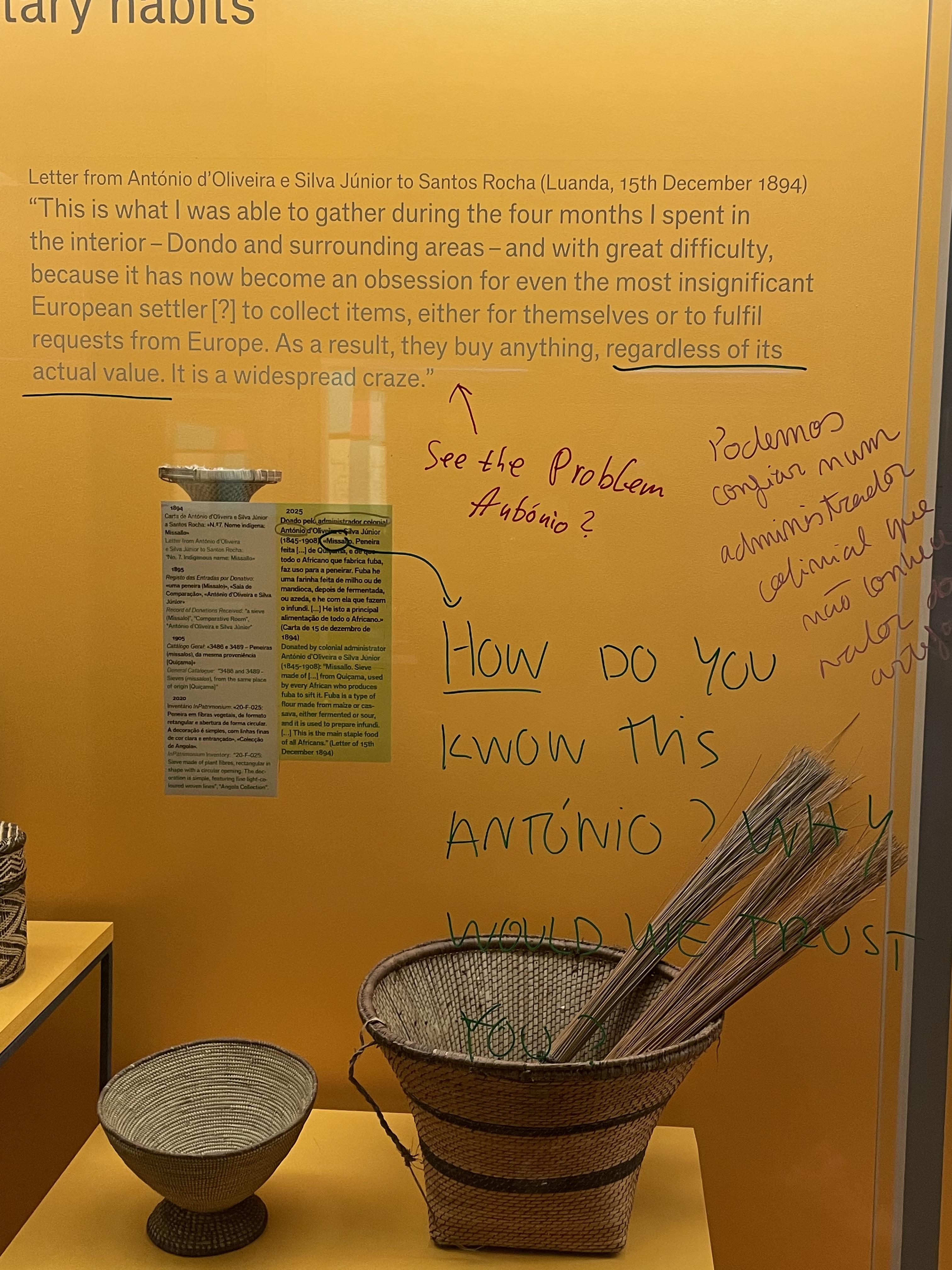

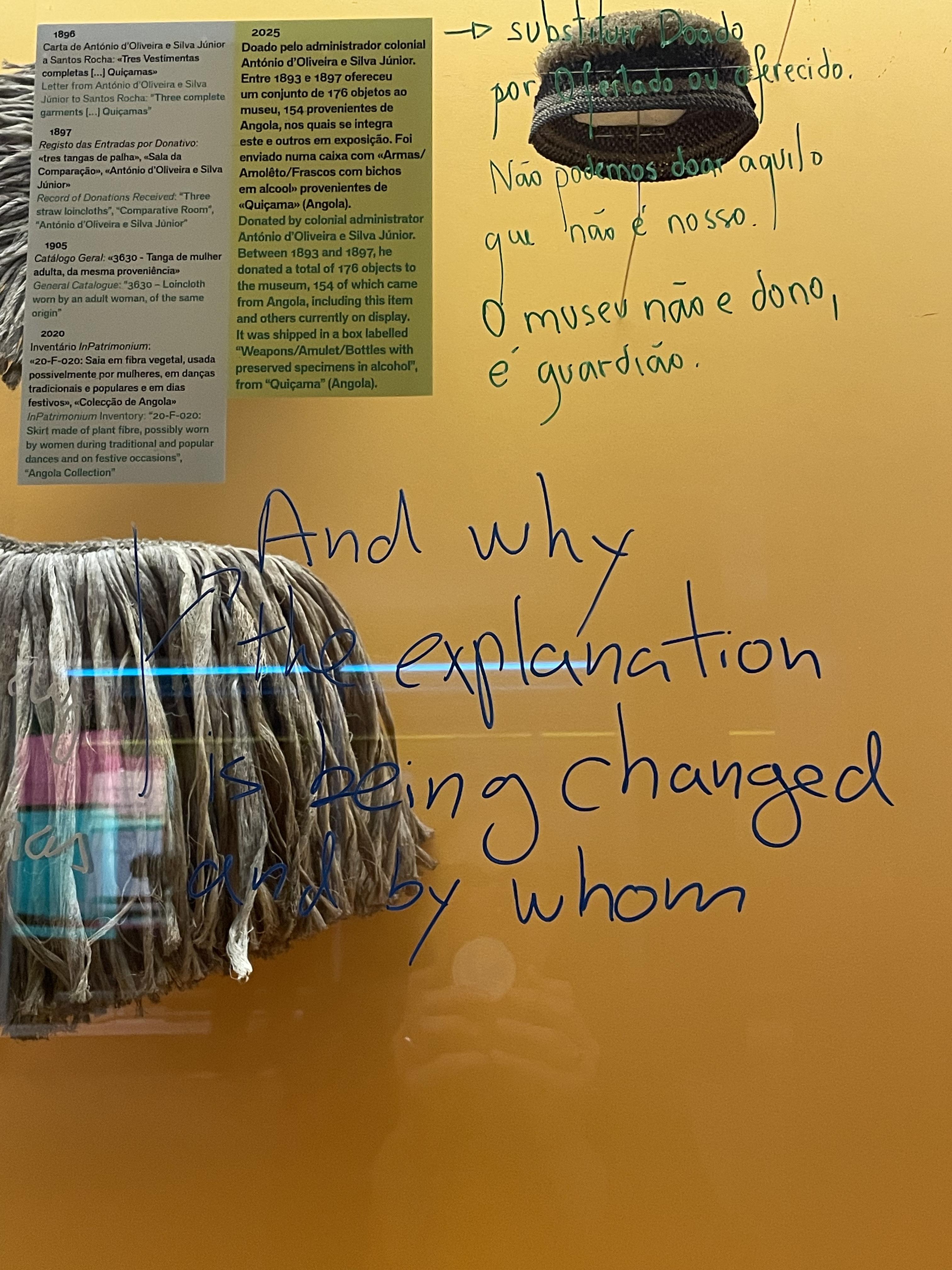

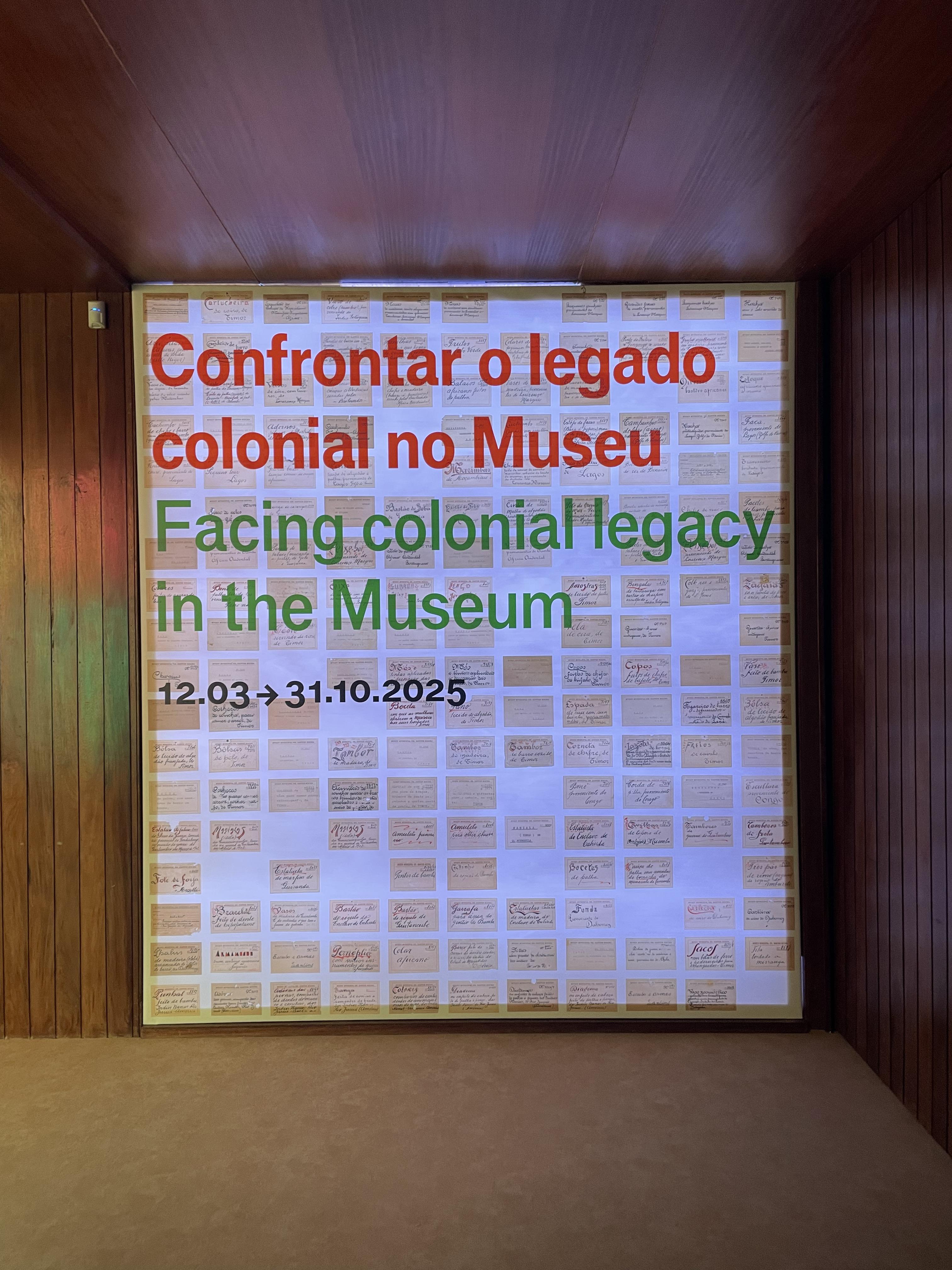

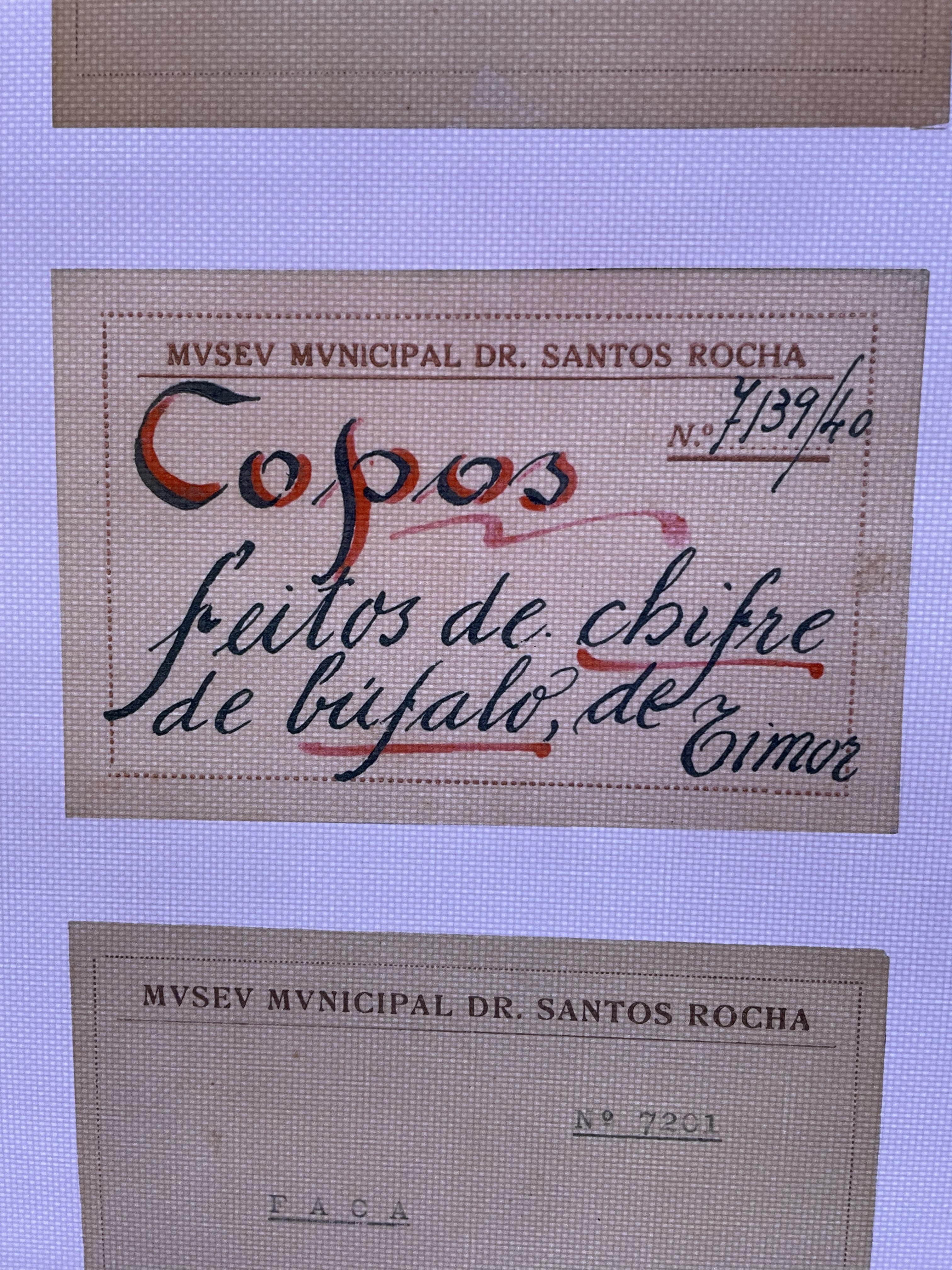

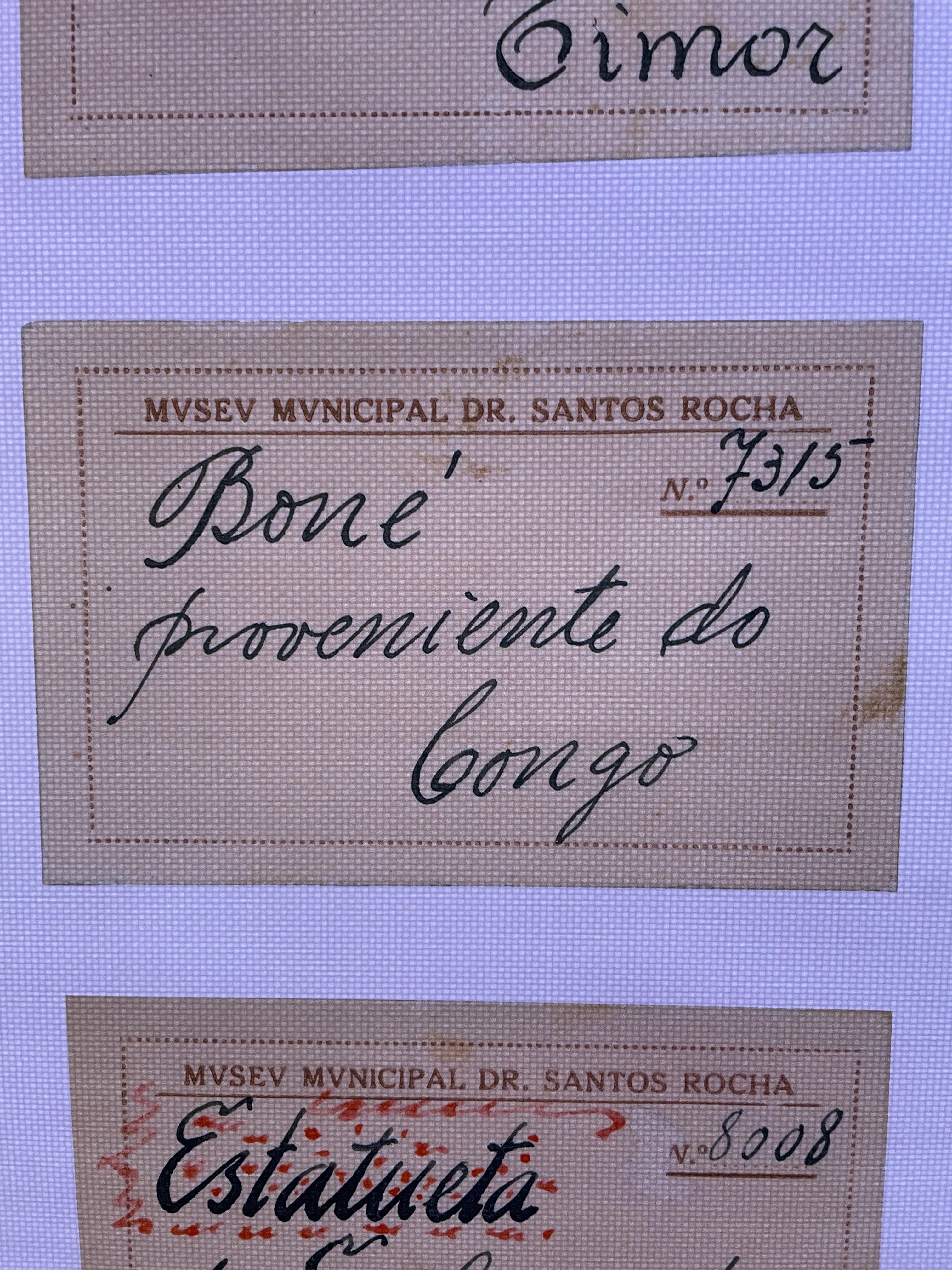

My research also led me beyond Lisbon, to the Museu Santos Rocha in Figueira da Foz, where the Transmat project had initiated a powerful intervention within the museum's permanent collection. Developed as part of an international conference on transdisciplinarity in museums, this initiative brings together scholars and curators committed to developing new methodologies for documenting and interpreting colonial-era collections. As part of the intervention, thought-provoking questions and concerns were inscribed directly onto the glass of the original exhibition displays. Some addressed the objects themselves, such as: Is this instrument still in use today? What sound does it produce? What does it mean to play this instrument within the culture it belongs to? Others challenged the language and framing of the exhibition, correcting outdated terms like "savage" or "uncivilized" and posing critical questions about provenance: Was this a donation or a looted object? The intervention also raised broader concerns about restitution, asking why European museums are often hesitant to return objects, despite the fact that many of these institutions have faced devastating losses themselves, through fires, conflicts, or other crises, yet still consider non-European institutions under suspicion when it comes to their ability to care for these artifacts. By inscribing these questions into the physical space of the exhibition, the intervention disrupted the assumed neutrality of the museum display, prompting visitors to reflect on the histories and power dynamics embedded in these collections. The intervention at Museu Santos Rocha exemplifies how contemporary museum practices can critically engage with historical collections, making space for alternative narratives and inclusive dialogues.

Reflecting on these experiences, I return to the symbolic resonance of Rua dos Navegantes. The street's name speaks to a history of movement - of people, objects, and ideas - that continues to shape cultural institutions today. Yet within museums like the National Museum of Ethnology and projects like Transmat, we see efforts to navigate these histories differently, charting courses that prioritize access, dialogue, and critical engagement. In this sense, the "Navigators" that matter today are not those seeking new lands to claim but those working to reconnect, reinterpret, and reclaim the past in ways that are meaningful for the present and future.